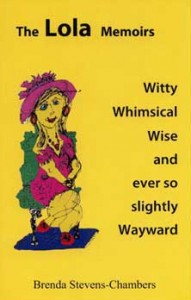

The Lola Memoirs

The Lola Memoirs

‘At first glance this is a simple little book. Brenda’s stories can be read between the lines. Textures, feelings and the small detail’s of a child’s world are revisited with adult hindsight, while sibling rivalry and competing for mother’s love, play out behind the scenes as a shadowy backdrop. Those unspoken experiences that shaped Brenda are here, layered, behind the humour.’ (Anne-Marie Roberts, Bendigo Weekly 28 May 2010).

Two Extracts:

Half way through her slab of pecan pie Lola looked out the window to see a pack of lycra-clad cyclists cruise onto the footpath. Lola loved lycra. She didn’t wear it herself, not with her bottom, but other people looked good in it. Especially, guys.

They might have ridden three mountains, but unlike the poor runner who staggers about after a marathon, lycra-clad cyclists needed no recovery. All they needed was an audience. Like male ballet dancers and movie stars, they enjoyed a little preening ? girlfriends, lovers, other guys, were happy to oblige.

Concealed behind a vase of flowers, Lola studied the cyclists. How they halted on the footpath but didn’t immediately disembark the bike. With one foot on the pavement, the other resting on the pedal, they posed, then dismounted, propped the bike on its stand. They stretched — elongated their torsos — such a pleasure in lycra.

The café door opened and the cyclists entered. Tall ones, short ones, chubby ones, thin ones. Not since the Renaissance had men had permission to wear such beautiful colours, or smell so bad, as a blast of perspiration hit Lola’s nostrils.

The Dove of St Paul’s – How Lola Got Her Name

Lola caught the lift to the third floor and turned left along Ward Three West to room eighteen, her mother’s room. An hour before she had received a call saying her mother had deteriorated and that she should come as soon as possible. Although there had been several such calls, Lola still dreaded the sight of her ailing mother. She would never reconcile the vibrant woman who had fretted over hems and wanted so much for her children, with the frail, sunken one that she was about to see.

Entering the room Lola was surprised to see her mother sitting upright, a cushion of crisp white pillows supporting her. She was dressed in a white nightgown and her hair was freshly combed, her lips made-up, and the fragrance of lavender water formed a halo of sweetness around her.

Lola kissed her mother’s cool cheek, drew a chair as close to her as she could, and took her hand, its frailty sending a chilly fear through her. ‘Now what’s up?’

‘Just a little dizziness, Dear. I said not to worry you, but the nurse got in such a spin, the poor girl.’

Her mother’s voice was calm, her face as pretty as ever. Although so close to death, she was content. For from her hospital bed she could see the red brick tower of her beloved Saint Paul’s, where she and Lola’s father had married decades before.

‘I’ve been waiting for you,’ she said.

‘You have?’

‘Yes.’

‘I have something to tell you. Did I ever tell you of the time your father and I were married, and we upset the minister.’

‘No, go on.’

‘Well, we were so poor and we wanted to do something special so we brought a dove into the church and we were going to set it free on the steps after the service, but the minister heard it cooing in your father’s pocket and wasn’t too pleased. Your father, shoved it in my dilly bag and ran into the hall to hide it. The only place he found not filled with trifles and sandwiches was the old ice chest in the hall and he shoved it in there. Someone had filled it with ice, but no-one thought to use it, so in it went.’

‘Go on.’

‘The years flew by, then one day the minister’s small daughter died from a terrible disease that had no cure. This little girl was like a gift from heaven for every time her parents took her down the street a sprinkle of rain would follow her so the gardens were the prettiest in Victoria. When visiting farmers, clouds would gather and it would rain, the sun would shine and the grass would grow and the cattle and sheep would frolic in the paddocks. But it only rained when the minister had his daughter with him. Soon there was standing room only at Sunday service and the minister was overwhelmed with invitations to tea and scones from his parishioners. The minister’s daughter grew exhausted trying to please everyone and that is how she died.

‘Everyone from miles around came to her funeral and the hall was filled with trifles and sandwiches. The organ played softly as the small white coffin was brought into church in the arms of the girl’s father. The choir was in fine voice and everyone was in their best black outfits.

‘Towards the end of the service, Aunt Betty who was beside me said, ‘Oh, I must put the kettle on,’ and tiptoed towards the hall. The next minute there was a loud swoosh and women’s hats fell off their heads as thousands of white doves flew into the church followed by Aunt Betty with the dove your father had hid in the ice chest the day we were married, perched on her head. Then, it fluttered down to the coffin and slowly, ever so slowly, turned to marble as did the humble little coffin.’

Lola had heard many a story from her mother but this was the best. How she wished she had spent more time with her mother, not wasted so much time working, travelling, lounging around in galleries, avoiding her when upset.

‘Now, Dear, what I am about to tell you, could upset you, but please don’t be angry with me.’ Her mother’s voice was the faintest whisper. Lola squeezed her hand in reply.

‘That little girl’s name was Lola. And that is where your name came from. I always told you I named you after Lola Montez, the singer, only because I wanted you to be bright and happy, not to grow up brooding over the poor little sick girl.’

How Lola had suffered for her name, being called Lola-lolly-bottom all the time. Then as she grew older and someone said that Lola Montez was a courtesan, she almost changed her name. ‘How could you, Mum?’ she asked, ‘a courtesan?’

‘I thought it was a fun name. No one ever mentioned that other business then.’

With a start Lola remembered the many times she had visited the country from her home in Melbourne to be told that she had brought the rain with her. Her name was more special than she realised. How she loved her mother for telling her now before it was too late.

Lola’s mother’s eyes closed, her breath was lighter than light as she beckoned Lola still closer. ‘Soon,’ she whispered, ‘I will take my place in heaven.’ She paused for breath then continued, ‘Upon my arrival I will be dining with the Father, and I plan to speak to him about the cathedral.’

Lola nodded.

‘And, you know how the best of intentions bring forth the best outcomes, well I can’t give you details but all will be well at St Paul’s, the doors will reopen and the bells will ring again.’

With that, a thousand white doves flew through the window. Lola watched in awe as her mother gently floated from the bed, white wings replacing her arms. And the doves, with golden halos of prayer appearing, formed an avenue of honour and her mother with a gentle flap of her wings flew to the front of the flock, through the window, and from the building.

Lola watched as the doves circled the children’s ward, the mothers’ ward, the cancer ward, and the loneliness ward. Then, with a purposeful flap of her wings her mother soared across the city to St Paul’s. There she led her flock in three circles of prayer. Each time rising a little higher until, their prayers complete, they merged with the feathery clouds above the steeple and into the heavens beyond.